MyStrengths Assessment Methodology & Development

Educators, therapists and business leaders are turning to MyStrengths as their go-to resource for strength insights for the simple, accurate and effective communication of personality strengths.

The MyStrengths Assessment has become one of the leading strength surveys, particularly for young people. It’s use of clear, simple language, age-specific examples and relevant application has made it powerful and accessible to a defined adolescent audience. The strength categories and trait descriptions get straight to the heart of each strength, bringing a clear understanding of self and identity.

And now, the MyStrengths Dashboard offers leaders a central hub for long-term interaction with the strengths and wellbeing of those you assess. [Learn more about how to use MyStrengths]

Below is the account of how the MyStrengths Assessment was developed, tested and rolled out to tens of thousands.

Building blocks of positive psychology

The MyStrengths Team have been passionate students of Positive Psychology. By definition, “Positive psychology is the study of what makes life most worth living” (Peterson, 2008). It is a scientific approach to studying human thoughts, feelings, and behavior, with a focus on strengths instead of weaknesses, building the good in life instead of repairing the bad, and taking the lives of average people up to “great” instead of focusing solely on moving those who are struggling up to “normal” (Peterson, 2008).

In short, where psychology focuses on what is wrong with people, positive psychology focuses on what is right with people.

Martin Seligman, known as the father of positive psychology, grew frustrated with psychology’s overly narrow focus on the negative; so much attention was paid to mental illness, abnormal psychology, trauma, suffering, and pain; while relatively little attention was dedicated to happiness, well-being, exceptionalism, strengths, and flourishing.

Dan Hardie and the MyStrengths team took the strengths model as a way to work with teenagers in private practice, helping them identify their best traits and work to enhance their wellbeing by growing what is good. It was often found that underneath the presenting need was a faulty view of self and their world; a damaged self-esteem that had an unhealthy obsession with weakness and fault, and very little clarity and belief in one’s intrinsic beauty, strengths and uniqueness.

The team took on Seligman’s belief that building on our strengths is often a more effective path to success (and healing) than trying to force excellence in areas we are simply not suited for. In practice, the team took the habit of diagnosing and identifying a client’s strengths and working to provide them with greater insights, practices and opportunities to use them (among other counselling techniques and tools).

Recognising inadequacy in other strength models

After using numerous strength assessment tools over years of therapy practice with adolescents, Dan Hardie and the MyStrengths Team felt frustrated with the confusing language and inadequate capturing of many important strength traits for an emerging generation. The existing tools felt like they were written for a more sophisticated audience, and the power of the strength insights was getting lost in the verbosity of description [See comparing the Top 3 Strength Surveys].

Case Study:

After using one of the more popular strength surveys, we received feedback from a mother whose son was on the autism spectrum. She stated, “none of the diagnosed strengths truly captured his incredible power of observation, memory or empathy. I had to translate the complex wording and try to come up with my own examples that might help (it was disconcerting that he received Judgement and Spirituality as strengths). The educated elite might understand these terms, but not my son. It felt frustrating for him and our family.”

It was the third client within a week who would feel disappointed after an exercise that was supposed to be incredibly insightful, encouraging and identity-forming.

Researching Strength Categories and Description for teens

Martin Seligman states that the 24 virtues studied and stated in the VIA Character Survey are not a conclusive or exhaustive list of personality strengths – they are only one way to study and describe strengths. While the VIA Character Survey (24 strengths), Clifton Strength Finder (34 strengths), WorkUNO test (24 strengths) and numerous other assessments have their own set of strength categories, the MyStrengths Assessment was developed within Australia with the view that there was a gap in defining, labelling and describing adolescent strengths; not to mention the strained process of logging on and accessing convoluted assessments.

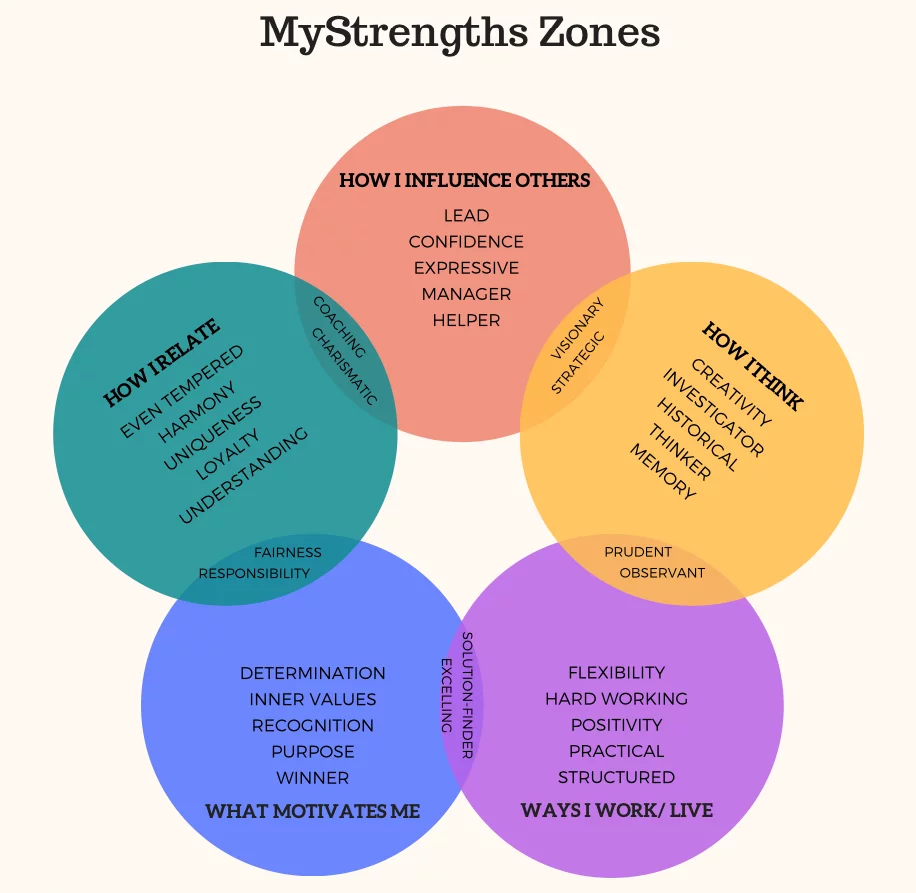

A three-year writing, research and testing process ensued, paying particular attention to the self-described strength traits of teenagers and the observation of their parents. We discovered that there were patterns and zones of strengths, with overlaps in the way each directs their relationships, energy, motivation and attention.

The set of strengths has morphed and changed over time, with greater sample sizes and adjustments in language. At 2020, the MyStrengths Assessment has settled on 35 key strength traits that sit within 5 Zones of function (defined in graph1)

Focus groups, school partnerships, and rigorous feedback

The methodology for creating the MyStrengths Assessment has been developed through a process of research, applied practice and key stakeholder review. The strength categories, descriptions and insight outlines have been formed from the continuing research and feedback cycle established from the thousands of psychologists, therapists, parents and adolescents who are engaged in the assess and review process.

While the MyStrengths platform was being written and informed by the research with adolescent focus groups, the larger scale testing has been done in partnership with strength-based schools who want tools that are accurate and effective in communicating with teens.

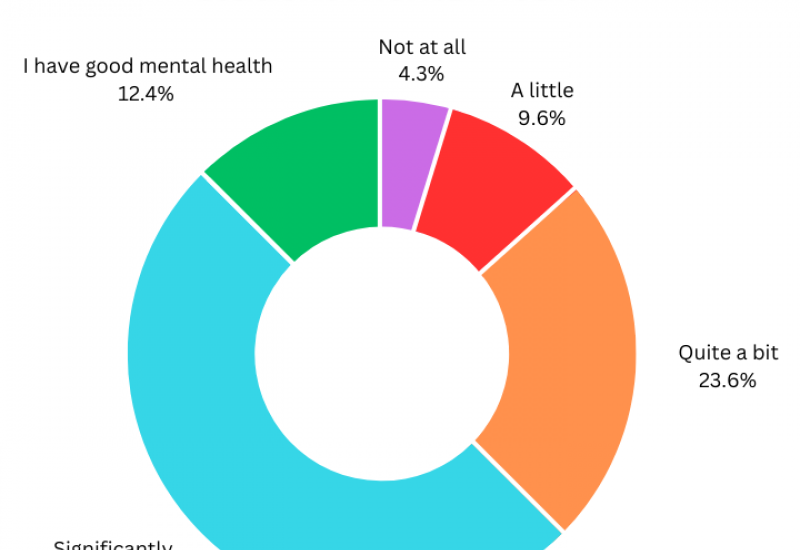

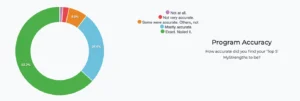

At January, 2020, over 26,000 teenagers have taken the MyStrengths Assessment. For any assessments – from GMATs to IQs – the continuous challenge is to ensure the reliability and validity of its results for the target audience. Within the MyStrengths Platform, every participant is asked to evaluate their results and measure the accuracy and readability of each strength. This continuous feedback helps to inform the redevelopment of both the assessment and strength content. Feedback over the proceeding 12 months has shown nearly 90% of participants report that their strengths are either “Exactly” or “Mostly Accurate”, creating one of the highest accuracy rates of kind.

As patterns emerge, we continue to make adjustments to the way we define, describe and assess the strengths.

Assessment Methodology

The MyStrengths Assessment follows the widely used self-reporting rating scale using subjective judgement of the participant. Starting with a presupposition, participants are asked to scale their response with their most automotive instinct. Categories are tested through a number of variant statements, some in the first person grammar (I/we), while others are in the second person (you/we) perspective. The number of variants and angles of inquiry contributes to the accuracy of the assessment.

Where some personality assessments involve a very lengthy log-in and assessment time (with one popular assessment having over 200 questions, taking over 30 minutes to find a result), MyStrengths has sought to establish a median assessment time of 10 minutes with a speedy User Experience and succinct interrogation, while maintaining accuracy of results.

Initially, the MyStrengths Assessment proceeded with a more lengthy tool of 175 questions, we found that there was less than 1% difference in proclaimed accuracy when we reduced the format to 105 questions. The 1% result was actually in favour of a shorter assessment, and the assumption is that teenagers often lose concentration and therefore accuracy after approximately 12 minutes of focused response time (a study in teen focus from FK Graham). A shorter assessment keeps participants on track and closer to the goal.

Top 5 Strengths

Many of the popular strength assessments produce a Top 5 strength traits, with an upsell to discover all of your traits in a row. MyStrengths has resisted the temptation to offer a long list of traits as the human brain is wired to move directly to the negativity bias, looking for our weaknesses and worst performing traits. In our view, this discredits the focus on strengths and does not allow a user to focus solely on their best self.

MyStrengths has experimented with the offering of 3 strengths, or expanding to 7 or even 10 strengths. However, studies have shown that a set of 5 strengths enables a participant to connect with multiple parts of their personality strengths, understanding that we are layered and varied.

MyCharacter Junior Assessment

Where the MyStrengths Assessment focuses on 15+ year olds, there has become an emerging request for an introduction to strengths for juniors. Testing among 12 year olds found that many of the common strength assessments were too long and difficult to comprehend, resulting in faulty or meaningless results.

MyStrengths took on a specialised research project in partnership with 3 Sydney-based high schools to produce a short, introductory Assessment for Year 7 students (12 year olds), helping them take first steps in understanding their uniqueness through the lens of strengths. The research team took the principles learned in the MyStrength Zones and came up with a reduced set of 20 traits that would encapsulate some of the most commonly recognised personality strengths in junior high students.

This project has resulted in the introduction of the MyCharacter Assessment, offering a shorter, simpler assessment that would help children understand some of their uniqueness and differences.

The team are now conducting wider testing and feedback, with nearly 5000 pre-teens having taken the MyCharacter Assessment. Reviews are underway, and will sharpen the accuracy, descriptions and labels within the assessment outcomes.

References

Seligman M & Csikszentmihalyi, M (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction, American Psychologist, 55, 5-14. Also Chapter 1 of Positive Psychology, a publication of mheducation.co.uk

Graham, F. K., & Hackley, S. A. (1991). Passive and active attention to input. In J. R. Jennings & M. G. H. Coles (Eds.), Wiley psychophysiology handbooks. Handbook of cognitive psychophysiology: Central and autonomic nervous system approaches(p. 251–356). John Wiley & Sons.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Adler, A. (2018). Positive Education. In Global Happiness Council, Global Happiness Policy Report 2018 (pp. 52-74). New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009) Positive Education: Positive Psychology and Classroom Interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35, 293–311.

https://positivepsychology.com/founding-fathers/

https://positivepsychology.com/what-is-positive-psychology-definition/